Pripyat and exclusion zone today

Pripyat of today is a ghost town. Despite its emptiness, the spirit of the ghost town is yet captivating. The town still lives while surrounding villages were leveled by excavators. Only rare road signs indicate their former existence. Pripyat just and the region in general are patrolled by the local militia. Despite their persistent vigilance, the town was looted multiple times during its aftermath period. The ruins are totally looted. Some say it’s impossible to find a single apartment in the town that was not visited by looters and emptied thoroughly.

The local military factory “Jupiter” worked up until 1997. Today, this facility is completely ruined and looted even more than town apartments. The town is covered with graffiti, town signs, books, and monuments of Soviet leader Lenin. Everywhere from hotels to local militia departments you can find something dedicated to the long forgotten socialist ideologist.

A slow stroll through the town feels like a trip to past. The surroundings look like a cinema studio. The decorations are intact but they look deserted and dead. Even birds abandoned this place. Imagining the cavalcade of energy and joy that once energized the town is not even close to being possible. The settlement rose from rubble on the green field near the CheNPP. Everything was made of concrete. All buildings look alike according to the trend picked up by Soviet engineers. Some buildings are covered with sprouts and underwood. Some are hiding behind trees.

Chernobyl is the most vivid example of how nature easily consumes what we build. In just a few decades, the whole area will look like nothing but ruins. It is a tragically exclusive place on Earth.

Chernobyl was a disaster for people, but for wildlife? Not so much

When the Chernobyl nuclear power plant melted down in 1986, more than 116,000 people were permanently relocated from a contaminated area comprising 4200 km2, an area that was later designated the Chernobyl exclusion zone.

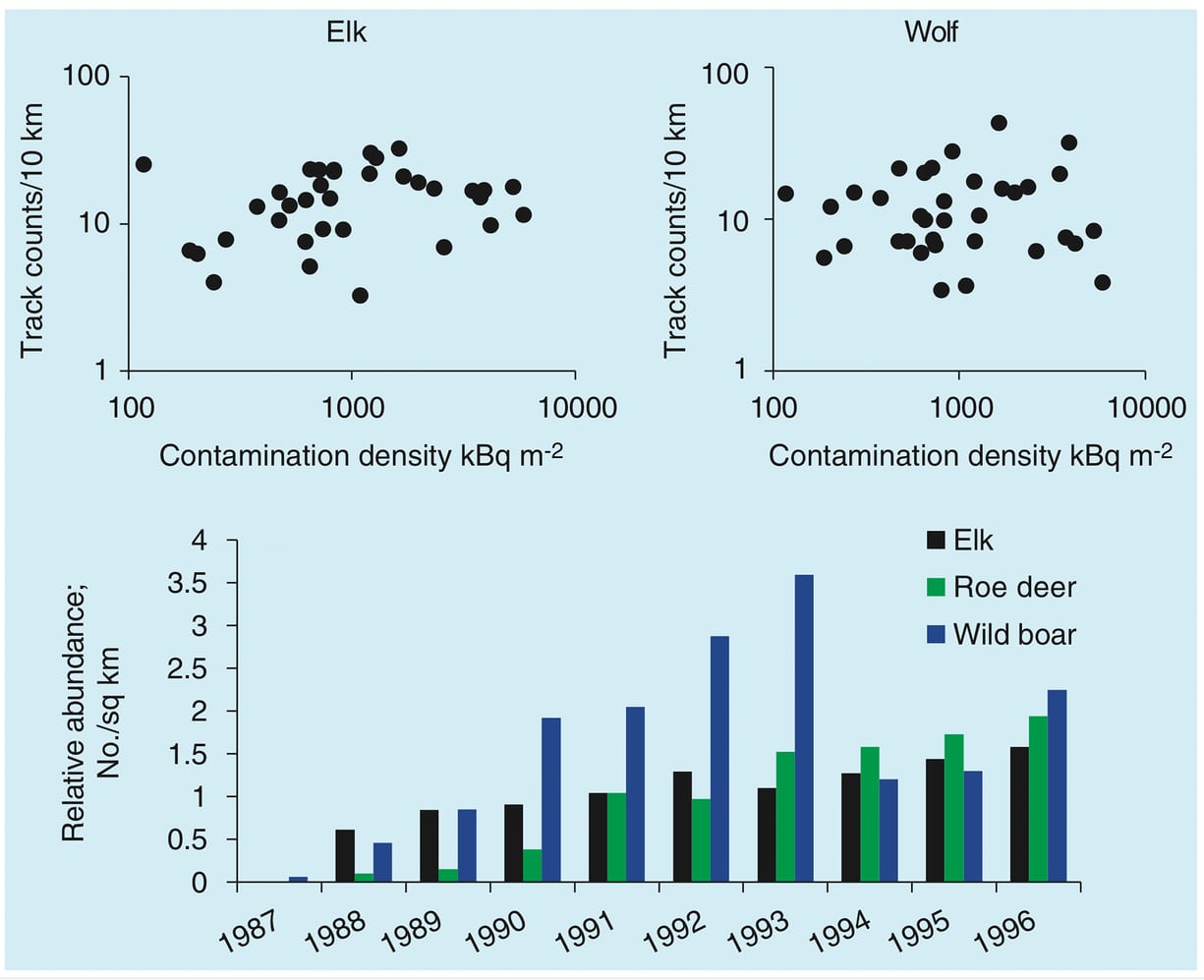

But what happened to the local wildlife? Previous studies indicate that wildlife numbers initially dropped in the months after the accident. However, thirty years later, what effect is radiation contamination having on the abundance of Chernobyl’s large mammals?

An international team of researchers, headed by Tatiana Deryabina of the Polessye State Radioecological Reserve (PSRER), conducted surveys to find out. The PSRER is the Belarus sector of the Chernobyl exclusion zone. It covers 2,165 km2 (half of the total Chernobyl exclusion area) and has similar radiation levels to the Ukrainian sector. The findings for PSRER were compared to four nearby nature reserves that were uncontaminated by the Chernobyl accident: Berezinsky Biosphere Reserve, a state nature reserve covering 852 km2; Braslav Lakes National Park, which covers 645 km2; Belovezhskaya Puscha National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage site situated both in Poland (105 km2) and Belarus (1501 km2); and Narochansky National Park, which covers 874 km2. Of these, just two (Belovezhskaya Puscha and Narochansky National Park) allow limited wildlife hunting.[1]

The team tested three fundamental hypotheses concerning the resilience of wildlife to the world’s worst nuclear accident:

- Hypothesis 1: densities of mammals were suppressed due to the levels of radioactive contamination in the Chernobyl exclusion zone

- Hypothesis 2: densities of large mammals were suppressed at PSRER compared with those in four uncontaminated nature reserves in Belarus

- Hypothesis 3: densities of large mammals declined between 1 and 10 years after the accident

To test these hypotheses, trained staff conducted wildlife snow track censuses between 2008 and 2010 along 35 permanent track survey routes (total combined length of 315 km with an average track length of 9 km). Specific PSRER habitat types (former agricultural lands, former villages, evergreen forest, and deciduous forest) and levels of radiocæsium contamination density were mapped using GIS along each of these routes.

Aerial surveys were conducted between 1987 and 1997 from February through early March when snow cover was present. The study area survey took place from a height of 100 metres at a speed of 70-100 km/h and extended to approximately 250 metres on each side of the helicopter.

As you can see, the empirical data show no evidence of long-term radiation damage to the large mammal populations at Chernobyl, and thus, the evidence does not support any of the three hypotheses being tested:

In fact, increases in elk (moose) and wild boar populations in the Chernobyl exclusion zone occurred in the early 1990s, when these species’ populations were undergoing a rapid decline in former Soviet Union countries due to increased rural poverty and weakened wildlife management.

Further, the relative abundance of wolves living in and around the Chernobyl exclusion zone site is more than seven times greater than in the four nearby uncontaminated nature reserves.

“There have long been rumours that the Chernobyl site has abundant wildlife — including carnivores — so I welcome this piece”, said wildlife demographer Tim Coulson, a Professor of Zoology at the University of Oxford, who was not part of this study.

“Because it is contaminated land, it is not easy to study wildlife in detail, and any studies are going to have to rely on approaches like this taken here”, said Professor Coulson in email.

In fact, this study demonstrates that, regardless of potential radiation effects on individual animals, the Chernobyl exclusion zone supports a thriving and abundant mammal community despite nearly three decades of chronic radiation exposure.

“It’s very likely that wildlife numbers at Chernobyl are much higher than they were before the accident,” said co-author Jim Smith, a Professor of Environmental Science at the University of Portsmouth, in a press release.

Chernobyl’s wild boar populations grew especially fast - until 1993-1994, when they suddenly crashed. This was due to a large increase in wolves, which are particularly fond of dining on wild boar, combined with an outbreak of African swine fever.

[1] During the preparation of the article were used the materials of the site https://www.theguardian.com/science/grrlscientist/2015/oct/05/what-happened-to-wildlife-when-chernobyl-drove-humans-out-it-thrived